This is a story about the day it all changed for me, and hopefully for other African and minority language speakers. It is a story about the day I had my “stroke of genius”. However, there was nothing particularly genius about this idea. It was all common sense, which, until this day, was not so common thanks to decades, perhaps centuries, of thinking in a particularly constrained manner.

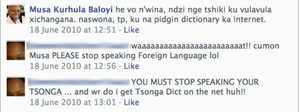

I was upset when I read the comment; No-one has the right to tell me what language to speak! But the conversation drove me to perform a quick Google search for an online Tsonga dictionary. To my surprise, no online dictionary existed! Instead I found dictionaries for almost all the other South African languages, and, if a dictionary or translator did not exist at the time, it was in the works.

In South Africa, there is a perception that all Tsonga people are from Mozambique, so they are excluded from most national services such as TV broadcasting. But Mozambique is not so keen on preserving, let alone developing, native languages. Although Zimbabwe and Swaziland are active in language preservation, Tsonga is a minority there, so no African governments are actively trying to preserve the language. I found websites claiming to offer translation services, but they were just that, claims.

So I said to myself, “If nobody will do it for us, I will”. This led to the creation of the First Online Tsonga Dictionary. But that was in June of 2010, and I still have not been able to do a decent fraction of all there is to do. With so few people and such little funding for a very large project, it is difficult to make much progress. I have failed to complete the translation of Google.co.za and Firefox. I am continuously struggling to add my hometown to Facebook and to update Wikipedia with the correct information regarding my people’s culture, our language and our geographical distribution.

Another challenge is finding the best translations that embody the intended meaning, not the literal one. Translators who do not fully understand the culture under consideration often fall into this trap. I am only one man, and there is a lot of information to research and to store, particularly when much of what has already been posted online is plagiarised or factually inaccurate.

Often times when I get to do research, I can’t share it with other Tsonga people because I am using the University of the Witwatersrand’s subscription to JSTOR and Google Books keeps toying with me by getting me interested in something and then saying I cannot read the next page.

So I have to post retyped paragraphs of what I find interesting, which Facebook will remove from the news feed before someone asks the same question again. Most of the people will never find out anymore than that. And that makes me very worried. History is best studied while it happens. Most people’s phones cannot read PDF files, so even when I find something publicly available, I have to take a screenshot or transcribe it. It is a lot of work.

But I am happy to say that I have made some progress. Through this project I have denounced the popular belief that Tsonga has ‘stolen’ every word it shares with another language. I have also translated the Agile Manifesto into Tsonga. My ncuva game is progressing well. So every now and then, I congratulate myself on the ideas I have been able to put into practice. But I have found that the technological challenges for the Tsonga exist for many minority language speakers around the world.

Internet-connected computers are a luxury for the masses. Information cannot only be for the educated, or the rich. And a lack of information, such as the underrepresentation of Tsonga music in the South African Music Archives Project, is dangerous. What is the other Tsonga music that was not archived? Why was it not archived? Who were the artists? Did they speak the same or a different dialect than mine? And the genre? Without answers to these questions in such an information-reliant society, how can my culture survive?

I cannot help but think the web has been designed with a Anglo-centric mindset, where one country speaks one language, but the African model is rather different. If the web were to be rethought and redesigned to cater for multilingualism, it would be a huge contribution to scientific advancement. I’m thinking something beyond simple translations from one word to another, or one script to another. I’m thinking of programs that recognise that, for Tsonga at least, ending a word in an “a” or “i” does not make much of a difference to the meaning: kokwani and kokwana both mean grandparent.

We need to curb digital colonisation by mapping “Ricatla” to “Rikatla”, “Ribolla” to “Rivolwa”, and “tchouba” to “ncuva”“. These are the same problems that the semantic web is trying to solve, but with an African twist. We need programmers to write Tsonga spellcheckers so that when I write “i” it is not instantly changed to “I”, “hina” to “hain”, “hoxa” to “hoax” or “mo” to “month”. I don’t like it when Microsoft Word underlines all my Tsonga words in red like there is something wrong with them. We need programmers who will make AdSense understand that “tintanghu” means “shoes”. Even better, we need programmers who will write tools just for these African and minority languages so that we can stop translating webpage by webpage. And hopefully these programmers will make us see that an abundance of native languages is not a curse but a privilege, just like an abundance of programming languages.

But to have an impact, these programmers must start a movement so big that GauTrain with their electronic systems, Absa with their small ATMs, Google, News24, and a host of other companies practising digital discrimination will no longer ignore the fact that Africans don’t just speak isiZulu and Kiswahili. There are languages like Tsonga, Gironga, Sheetswha, Txicopi, Bitonga, Cindau and thousands of others.

Other than my project Madyondza, there are attempts at digitising regional content such as Xitsonga Online, Tsonga Online, Tsonga History Discourse, Nthavela, Matimu News, and Ray Chauke’s YouTube channel, to name a few. It is not a big feat, but it’s a foot in the door.

It is high time we started to rethink digital colonialisation, and introduce online society to ideas such as tribes, clans, language families and dialects. We can derive value from this approach and instead of localising to fill our own pockets, consider localising to open up new lucrative markets for the locals. After all, they know their languages best. It would be a crying shame if we were to exit the Information Age without using information to change how people see themselves. Since most interactions today happen on the Internet, content can change the definition of what it means to be a minority.

I am not advocating this because I am holding on to the last few shreds of what is left of my heritage, I am advocating this because I have learnt that intelligence knows no language. Human advancement is losing out while we adapt tools built for other environments to suit our own. Those other environments never get to benefit from our intellect, and we surely don’t have the best tools at our disposal. A lot of time is wasted trying to translate each and every page instead of building tools that will do this automatically; time that could be dedicated to doing other important things. Wouldn’t it benefit human knowledge if the web was a facilitator for the formation of information links between different tribes, clans and languages? History is no longer written by the victors, but also the defeated. I don’t know whether I’m a victor, but I do know that I deserve to write my story.