Security of our information over the internet is increasingly hot topic after the revelations of the last few years. It's now more important than ever that software developers as well as testers understand security and the implementation details of the current standards. HTTPS is one of the protocols widely used to enable secure communication. It is absolutely necessary when accessing your bank accounts through online banking system, buying a book on amazon or doing any other financial transaction. So lets take a deep dive into HTTPS and see how it actually works.

HTTPS isn’t actually a protocol in and of itself. It’s actually HTTP over the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) or Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocols. TLS is the successor to SSL and the focus of this deep dive.

There are two parts to TLS protocol:

- TLS handshake protocol

- TLS record protocol

The TLS handshake protocol is used to establish a secure connection as well as to authenticate* (not to be confused with authorise) one or both of the parties who want to communicate. TLS record protocol is used to secure application data and to verify its integrity and origin.

TLS Handshake - part 1

The handshake protocol uses a series of messages to negotiate a secure connection. All but the last messages are plaintext. This means they are visible to anyone listening on the channel. The last messages sent by the client and the server are encrypted. Even though the messages are sent in plaintext, Diffie–Hellman key exchange protocol guarantees that the eavesdropper won’t be able to derive the keys used for encryption.

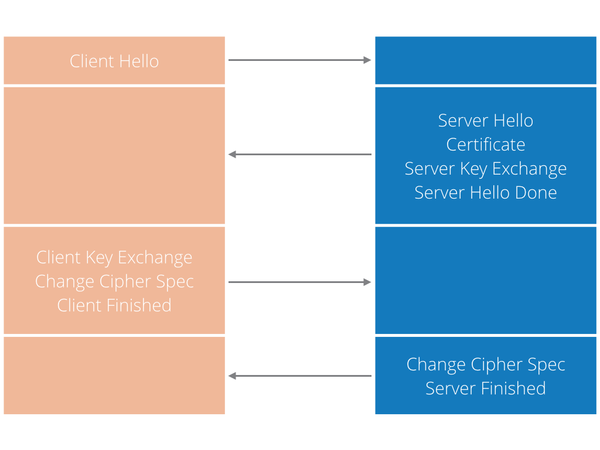

The following is an illustration of the messages that the client and server exchange.

The handshake is initiated by the client who sends the initial “Client Hello” message. The most important information this message contains are:

- Version number - The client should send the highest version number it supports.

- Randomly generated data - a 32 byte number which includes client’s date (4 bytes) and a randomly generated number (28 bytes). This number will be used with server random value to generate a master secret, which will then be used for encryption.

- Session ID - this is optional and if provided may be used to continue a previous session.

- Cipher suites - a list of ciphers that client supports.

- Compression algorithm - at the moment there is none supported.

The server then responds with a “Server Hello” message. This message will contain:

- Version number - the highest number supported by both client and server.

- Randomly generated data - similar to what client sent to the server, the server will now send another 28 byte random number, which the client uses to generate a master secret.

- Session ID - this is optional and is used to tell the client if this is a new session or not as well as if this session can later be resumed or not.

- Cipher suite - the strongest cipher supported by both client and server.

- Compression algorithm - specifies the compression algorithm to use. At the moment there is none supported.

Certificates

The next step is to authenticate the server to make sure it is who it claims to be. We do this through digital certificates. The Certificate is essentially a document, signed by a trusted authority and, in context of HTTPS, is used to verify identity of the domain.

In modern cryptography there are two families of algorithms - symmetric and public key. Both of these are used by TLS.

In symmetric encryption algorithms, the key used to encrypt the plaintext is the same as the key used to decrypt the ciphertext.

Public key encryption is used during the TLS handshake to authenticate the server and establish a new key, which is then used for symmetric encryption for data transfer. Public key algorithms have a key-pair (k1, k2). Both of these keys can be used to encrypt or decrypt, but only the other can perform the inverse. This key-pair is also called a public/private key pair. I've used indexes 1 and 2, but either of them can be used as the public or private key. The important part is that if 1 is used as public then 2 has to be private - and vice versa.

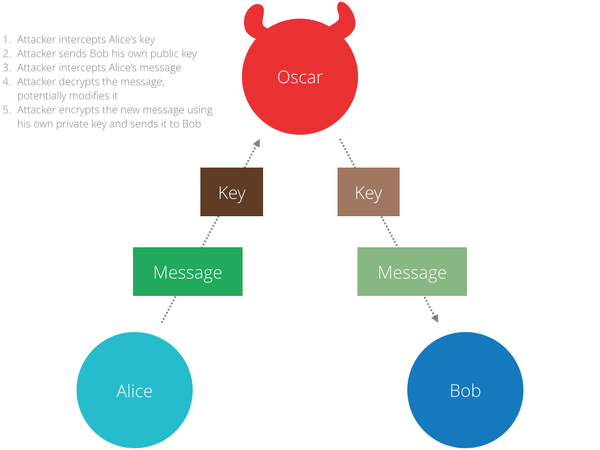

Public key cryptography is central to digital certificates and it works like this. Alice and Bob want to be able to send each other private messages. To do that Alice needs to send Bob her public key. Oscar places himself in between Alice and Bob. When Alice sends Bob her public key, Oscar replaces it with his own public key. When Alice next sends message to Bob, Oscar intercepts it, decrypts it using public key that he acquired, reads the message and encrypts the message using his own private key now. Oscar then sends newly encrypted message to Bob who has no idea that the message was already opened.

The solution to this problem is what is called a public key infrastructure (aka. PKI). One of the elements of PKI is a Certificate Authority (CA). A CA is an entity who issues digital certificates. Every browser comes with a set of CAs that it trusts called Trusted Authorities (TA). TLS uses these certificate authorities (CA) to vouch for identities of web sites. In essence, if you get a public key from Alice, you can check with a trusted authority (TA) whether that is really Alice’s public key or not.

>> “How do we establish a trust relationship in the first place?”

Another problem that comes up is how do we establish trust relationship in the first place? How do we know that we are talking to a CA and not some man in the middle (attacker)? Public key cryptography can help us here too! This time, public/private key-pairs will be used to sign/verify certificates. It works like this. Instead of encrypting the data with private key, the sender (Alice) encrypts a small piece of data (a token) and sends both ciphertext and plaintext, which are together known as digital signature, to the receiver. The Receiver, who receives the digital signature will then use the sender’s public key to decrypt the encrypted part of the signature. If the token and decrypted message match, the receiver can be sure that the digital signature had to be produced by the owner of the private key.

This approach allows one party to “vouch” for another. One trusted party (CA) can sign the public key of another. The recipient can check the signature and if he trusts the signer he can be assured that the public key belongs to the bearer. This assumes that a trust relationship is established with the CA. This relationship manifests as a predefined set of certificate authorities that the browser trusts. Each browser vendor is free to choose the set.

TLS handshake - part 2

After the server sends a “Server Hello” message, it will also send its certificate. The client will verify this certificate and if the verification is successful it will proceed with the handshake.

At this point the client will send a “Client Key Exchange” message. This message contains premaster secret computer using both (client and server) random values and is encrypted using the public key found in server’s certificate. Both parties compute the master secret locally and derive a session key from it. If the server can decrypt this premaster secret then the client is assured that the server has the correct private key. This step is crucial to prove the authenticity of the server. This message will also contain a protocol version that is necessary to prevent the attacker from manipulating the message, and tricking the client and server into using earlier a version of the protocol which is less secure.

The next message the client sends is “Change Cipher Spec”. This is almost the end of the handshake and notifies the server that the messages that follow will be encrypted (using negotiated parameters).

The client will also send a “Finished” message, which is a hash of the entire conversation to this point and is the first message that is encrypted.

To fully complete the handshake the server needs to reply with:

- “Change Cipher Spec” message, which is used to tell the client that the messages that follow will be encrypted using the parameters just negotiated .

- “Finished” message, which is a hash of the entire exchange to this point. If the client can successfully decrypt and verify hashes it is assured that TLS handshake was successful and the keys computed by the client are same as those computed by server.

After the TLS handshake is complete, the client and server have established security parameters (cryptographic algorithm, key, etc) that will be used for communication. From this point on the client and server can use a secure communication channel to exchange messages. They can also be assured that the messages exchanged are between the intended participants.

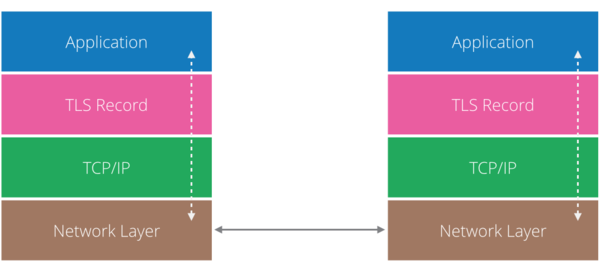

From this point onwards, any HTTP requests will be sent using TLS Record protocol, which means the actual payload, after first being encrypted by the sender and the receiver, will have to verify the payload and decrypt it. The following illustrates the layers the payload goes through.

Summary

In this short article we saw how HTTPS provides secure communication channel between client and server. For most readers, this will be enough to understand basics. But for those who are would like more details, I encourage you to look into certificates and how they work, the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange protocol, as well as openssl - an awesome tool that can be used to “dissect” TLS.

*Authentication verifies who you are. Authorisation verifies what you are authorised to do.

Sign up to receive the latest edition of P2 Magazine.