If you’ve been developing software in the last couple of years, you have probably encountered a tool like Cucumber, JBehave or SpecFlow at some point. These tools are intended to assist teams in practicing behavior-driven development (BDD), and some of our biggest clients use them—in many cases because we introduced them. But today I urge you to choose a different path.

What is BDD?

BDD was pioneered by Dan North, who felt that developers had been focusing too much on specific units of logic within software systems. He wanted to write software that was more focused on user behavior. He decided that the best way to do this was to create a process that enables everyone connected to the system’s development to use a common language for expressing user behaviors.

North’s ideas eventually led to the creation of tools that allow plain English statements to execute automated tests. These tools accomplish this end by mapping lines of text to specific blocks of code via regular-expression matching. When the plain English statements are run, the underlying blocks of code execute. The code blocks can be anything, but BDD tools are commonly used to execute functional tests using technologies such as Selenium or Watir.

Objections

Regular-expression mapping

The first reason why I object to using BDD tools is their most obvious and most problematic aspect: regular-expression mapping. As soon as steps with variables are added, it’s no longer easy to move cleanly between a step definition and where it’s used in a test. Consider these example steps from a project I worked on for a large airline:

Given I have booked a flight

Given I have booked a one-way flight

Given I have booked a flight with an unaccompanied minor

Given I have booked 2 flights

These steps are fairly similar to one another, but it’s difficult to know from looking at them which part of each step is a variable. Some IDEs have plugin support to assist with mapping steps to definitions, but you still end up having to search for partial text or browse through long lists of steps.

Regular expressions have a reputation for having unexpected edge cases, which is usually addressed by surrounding them with unit tests. This is technically possible, but it’s rarely done in practice. I would suggest that unit-testing your functional tests is a warning sign that your tests have become too complicated. Even without regular expressions, functional tests are the most expensive tests to write, run and curate—not to mention manage and keep green. Adding more complexity in the form of maintaining regular expressions is a cost you can and should avoid.

Step interdependencies

My second reason for avoiding BDD tools is the issue of interdependencies among steps. Consider the following example:

Given I have added a Darth Vader Poster to my shopping cart

When I complete my purchase with bitcoins

Then I should see my confirmation details

To test what the user should see on the confirmation page, you need to save some information from the previous steps. In this case, information about the specific product purchased must be saved, as well as the mechanism for payment. Saving state is a normal practice for tests, but the way BDD frameworks accomplish this is problematic.

In the example above, to save information about choices you have made within the step definitions for the Given and the When, you need some code within the step definition that saves the fact that you’ve chosen to buy a Darth Vader Poster and that you paid with bitcoins. Once you’ve saved this information, you need to be able to retrieve or modify it. The steps used in a test have no enforced order, so now every step created must be able to access the information saved by all other steps. For this reason, a feature of BDD frameworks is that state saved in each step definition is shared globally with all other steps. At the risk of stating the obvious: Global state is usually considered a bad thing.

“It’s tempting to write clever steps that sidestep problems with conditional logic and defaults, but this quickly becomes a dark rabbit hole.”

Global state isn’t the only disadvantage to this approach. The dependence of steps on other steps also introduces complexity. For the third step in the above example to run, certain specific steps need to have preceded it. Unless the first two steps save details about the poster and the payment method, the third step can’t assert anything. Someone not intimately familiar with the code has no way of knowing what each step saves and what data other steps rely upon having access to.

It’s easy to construct a seemingly valid (from a user perspective) scenario that nevertheless won’t work because of the underlying dependencies. It’s tempting to write clever steps that sidestep these problems with conditional logic and defaults, but this quickly becomes a dark rabbit hole. By the time your test code is clever enough to handle whatever can go wrong, it will be as complicated as your application itself.

Alternative tools

A BDD tool’s value proposition supposes that internal stakeholders communicate through plain English statements, and that such statements are easier to understand than code. In most cases these stakeholders need to present their vision not just to the development team, but also to external stakeholders. For that purpose, they certainly will not limit themselves to English statements. For example, the Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic (VAK) learning model demonstrates that if you want to present an idea or share information, you need more than just words to get many stakeholders engaged. Even if you don’t buy into the VAK model per se, using tools such as mock-ups, slideshows, or financial models—as well as plain English—will help to present the vision to external stakeholders. Reverse-engineering these multifaceted requirements into a BDD tool is just not worth the effort or complexity overhead.

“If the business is really interested in participating in test specification, this would be a great opportunity for them to pair with someone familiar and comfortable with the test suites the team has created.”

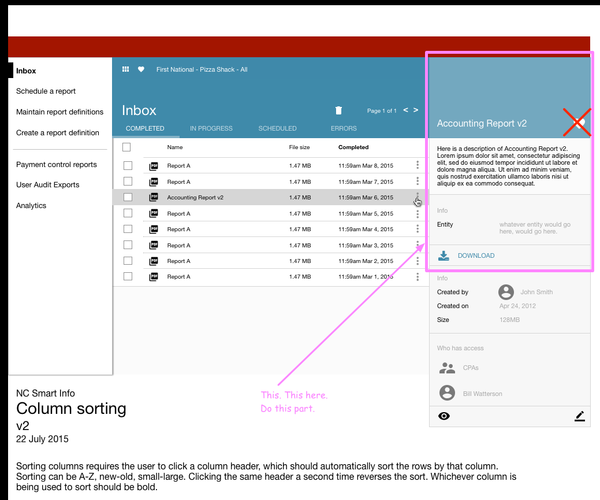

Mock-ups (like the one below), pictures, charts, photos, user research, interviews, analytics, documentation and conversations are some of the real ways teams understand behaviors. It takes team expertise to convert all of these things into a working application, and the team should feel free to express those behaviors however they see fit.

You still need tests

You still need tests, but that doesn’t mean you should explicitly combine your requirements and your tests via a BDD tool. Tests should be written by the team at the appropriate level based on their understanding of the feature under test and its specific requirements. These tests should follow the guiding principles of the test pyramid, which includes an emphasis on writing lower-level tests when possible because of their speed, reliability and low cost. These layers of tests will represent the living documentation of the application. It is a responsibility of the team to keep them updated and to ensure that they represent the application’s behaviors. If the business is really interested in participating in test specification, this would be a great opportunity for them to pair with someone familiar and comfortable with the test suites the team has created.

Most situations still call for some functional tests, but there’s no need to use a heavy BDD tool. For your functional tests, use a framework traditionally used for unit tests, such as JUnit or RSpec. Name your tests and methods well, so that it’s possible to quickly understand the test even without a technical background:

As you can see from the example above, it is not hard to translate the previous example’s statements into method names so that even nontechnical stakeholders can quickly understand what’s being covered.

Sign up to receive the latest edition of P2 Magazine.